Transport

From the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the development of the Canal du Midi created the first transport revolution in the South of France. This water-borne trunk road made it possible to take the Languedoc vineyard trade far and wide. First linking the two economically complementary regions of the Bas-Languedoc and the Haut-Languedoc, it the permitted the transport of cereals from Toulouse to the Mediterranean and the expansion of the whole wine economy with sales to Toulouse and beyond, in the first major expansion of the market.

The canal later came under direct competition from the Bordeaux-Sète railway line, opened in 1857. With the invention of light railcars in the 1880s, the railway became the most efficient transport route for wine marketing. The second half of the 19th century was an exceptional period of prosperity which raised standards of living for almost all social categories in the region.

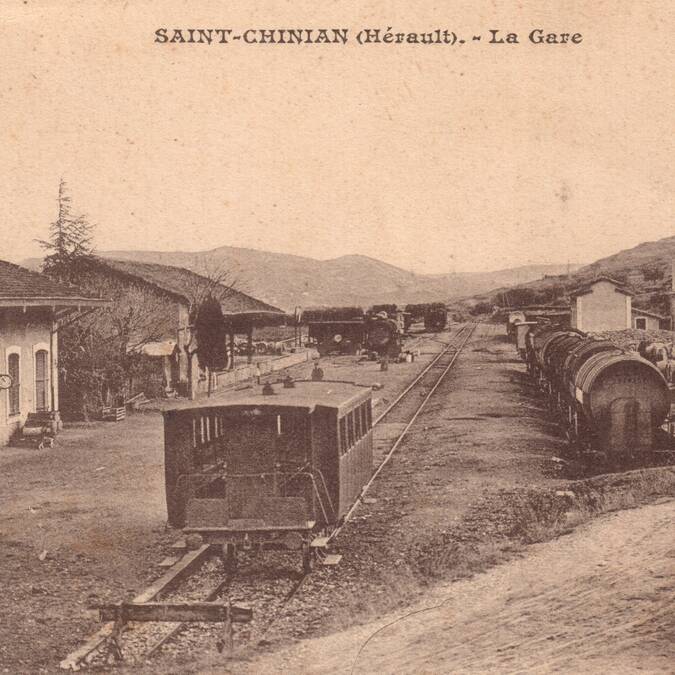

At the end of the 19th century, the deployment of a local rail network contributed to the opening up of the territory to the wider world, allowing the transport of additional resources and participating in the new dynamic of the ancillary trades - agricultural products, hoops and chestnut wood for barrels, alongside flour, iron and, of course, the wine itself.

Wine monoculture

It was not until the mid-eighteenth century and in particular the "freedom of plantation" finally allowed by an ever interventionist state, in 1759, then the free movement of wine in 1776, that the wines of the Languedoc really started to become famous. Until then, the area under vine cultivation never exceeded 20% of the arable land. The transition to a near monoculture, which took place between 1750 and 1850, was a true agricultural revolution.

The phylloxera epidemic

Phylloxera, a small aphid pest native to the United States, brought a death knell to the French vineyards in the late nineteenth century and, with such reliance on the vine, the regional economy was seriously damaged. Observed for the first time in 1863 in the Gard, the disease spread from east to west and caused the death of all vines within 3 years. The consequences plunged the entire French wine industry into a terrible crisis.

The plain of Biterrois and its surroundings are were affected later, after around 1880. The fall of production of the other regions was at first a boon as the needs of consumption remained stable. When phylloxera finally reached the southern vineyards, research had made a great deal of progress the remedies could be called-upon.

The vineyard were reconstituted with rootstocks from American plants naturally resistant to the insect. The number of grafts and replantings was a titanic work, and many Spanish workers were called in as reinforcements.

The crisis of the late nineteenth century

To cope with an ever increasing demand, the very high-yield Aramon and Carignan grape varieties, (which they said "made the vine piss") were grafted onto the imported root stocks throughout the South. The race for yield to cope with a considerable increase in consumption, especially in the working class and in Paris, led to an economic frenzy and the falsification of wines and fraud were absolutely rife. Wines were diluted, mixed and sold in the wrong bottles. Even artificial wines (without fresh grapes) were used, using raisins and elderberry juice. It was not until 1889 that the law gave a legal definition of wine, with heavy penalties for contraband. At the same time, Algerian wines were beginning to be imported via the port of Sète, competing directly with regional production and destabilising the market.

From 1891, the Languedoc entered a crisis of overproduction. The price of wine collapsed, with a hundred litres selling for just 5 francs despite production costs of 8 francs. The large estates fell into penury, while small producers went under.

The creation of professional unions was allowed by law in 1884, and vine growers quickly made use of the freedom in the face of a real social struggle with great inequalities between on the one hand large and small owners, on the other hand the power of the negotiators, essential intermediaries at the time for the distribution of wine in bulk. In 1904, the first strikes against the owners broke out at the Château de Sériège in Cruzy, before spreading to the neighbouring municipalities.

This crisis, linked to the imbalance between supply and demand, grew worse at the beginning of the 20th century. In this context and following the model of the Jura dairy cooperatives, the cereal cooperatives in the north of France and the Alsace wine cooperatives, the South of France saw its first wine cooperatives created in 1901.

A social and political revolution against the capitalism that had hitherto overseen the winemaking sector, the cooperative movement caused a change in the organisation of the industry. Winemakers went beyond the principles of wholesale to constitute new ways for sharing production tools, giving access to facilities and modern equipment, shared by the members of the commune. The changed social structure that emerged from this radical culture still has its echo in the motto of the cooperatives today - "All for one, and one for all".